Connecting LLMs to chemoinformatics

- 4 minsIn this article, expect to see a mix of my personal insights, high level overviews and a few technical deep-dives into LLMs and chemoinformatics.

Background

Over the past 8ish years, I’ve been working professionally across various aspects of drug discovery. Early on in my career, I focussed a lot on applying chemoinformatics techniques to make natural product discovery more effective. In my current role, we’re developing strategies to make data more discoverable and accessible using LLMs within clinical trial operations. As I started to dig into one of the more common techniques for this, retrieval augmented generation (RAG), I began to see a ton of similarities to how we used to search for chemical structures.

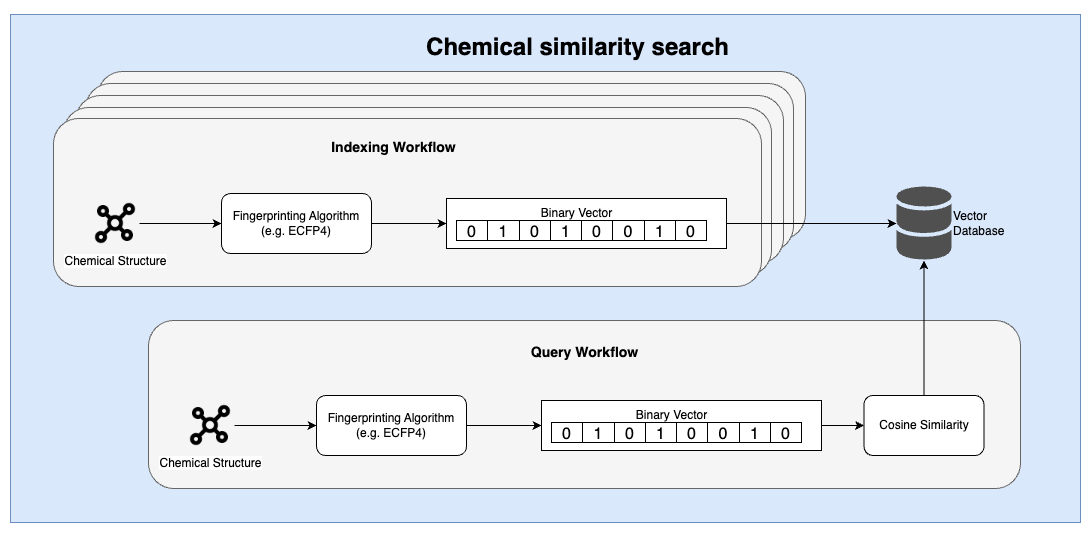

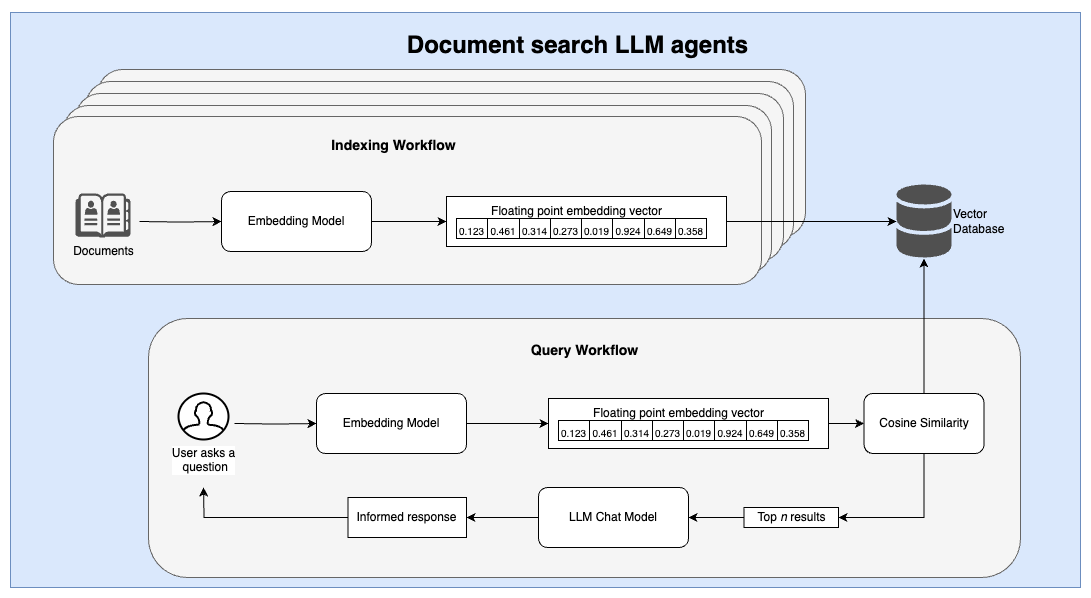

Both of these techniques rely on the core concept of vectorizing a complex input, storing this information in a specialized database and then doing simple distance measurements. These are demonstrated in the workflow images depicted below.

Similarities between the two workflows

At a high level, there are several thematic similarities between the two workflows. First, an embedding model (or algorithm) is used to ingest a complex input and translate it into a simplified representation that can then be indexed. Second, a similarity search is conducted using a relatively simple distance measure. These distance measures can be performed using highly optimized vector databases.

In both workflows, an indexing and querying pipeline is required to ingest and index data into a database prior to individual user queries.

Differences

Chemicals vs unstructured text

Abstract unstructured text is far more complex and unpredictable than the typical kinds of organic chemical structures that are usually queried in drug discovery.

Chemical structures are often stored in a text-based format called SMILES. Over the past decade, there has been significant research on leveraging advances in language models to ingest and generate novel chemical entities, known as generative chemistry. Unlike unstructured text that may provide narrative stories over long context windows, chemical structures have a fixed length with the majority of drug-like molecules containing fewer than 1,000 tokens. Drug like molecules also only have a small number of letters (atoms) have to follow a set of chemical rules (e.g. max number of bonds per atom) that limit the overall complexity of the data structure.

Working with simpler data structures meant that we were able to use simpler encoding methods (see more below).

Embedding models vs hashing algorithms

Embedding models for text are trained on large amounts of text data to better group text-based concepts. In the past, strategies like word2vec were used to convert words into vectors that retained some degree of sematic understanding. Today, embedding models are much more sophisticated than this and can relate abstract concepts not only across words but across varying lengths of multi-lingual text.

In the chemistry side, the most popular embedding strategy was something called the circular fingerprint. Here, individual atoms were profiled according to their surrounding environment to generate a unique hash. This hash was then converted to a number between 0-1023 using a bloom filter to generate a fixed-length binary vector.

This is not a perfect difference, simpler strategies (like word2vec) were used in NLP while more complex ML based systems have been employed and are continuously being iterated upon in the chemoinformatics domain.

Vector databases

At the time, for most of my research career, chemical similarity searches were done in a Python script where I performed a nested for-loop to compare my set of query molecules to everything in our database. However, when building more end-user focussed systems, I have used the RDKit Postgres cartridge to simplify molecule indexing and similarity searches.

Today however, there are so many vector databases to choose from that support vector indexing and distance based queries out of the box. Tools like ChromaDB as well as extensions for common databases like Elasticsearch and Postgres allow for RAG-based agents to be built very easily as extensions on top of existing databases. The open-source community and tools for LLMs are much more developed (not surprising given the recent LLM hype), but this could definitely help if I try my hand out at some chemoinformatics again soon!

One of the biggest challenges for building chemical databases wasn’t necessarily the chemical structures themselves but handling all of the unstructured metadata that accompanied each entity. It almost makes me wonder if we could build a better chemical database using LLMs to embed and contextualize molecular properties currently stored in text form.

If you like more content like this, let me know! Reach out on LinkedIn or leave a comment below.